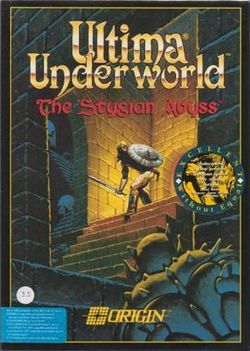

Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss

| Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Developer(s) | Blue Sky Productions |

| Publisher(s) | Origin Systems |

| Designer(s) | Paul Neurath, Doug Church |

| Composer(s) | George Sanger, Dave Govett |

| Series | Ultima |

| Platform(s) | DOS PlayStation (Japan only) Windows Mobile FM Towns |

| Release date(s) |

|

| Genre(s) | First personperspective, Adventure, Action RPG |

| Mode(s) | Single player |

| Media | Floppy disks (4), CD-ROM (1) |

Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss is a first-person computer role-playing game (CRPG) developed by Blue Sky Productions (later Looking Glass Studios) and published by Origin Systems. Released on March 27, 1992, the game is set in the fantasy world of the Ultima series, and takes place inside the Great Stygian Abyss—a large, underground cave system that contains the remnants of a failed utopian civilization. The player assumes the role of the Avatar—the Ultima series' protagonist—and attempts to find and rescue a baron's kidnapped daughter.

Ultima Underworld was the first role-playing game with true three-dimensional (3D) graphics, and it introduced many technological innovations, such as allowing the player to look up and down. Its design combines simulation elements with concepts from earlier CRPGs, including Wizardry and Dungeon Master; this led the game's designers to label it as a "dungeon simulation". As such, the game is non-linear and allows for emergent gameplay.

Ultima Underworld received widespread critical acclaim and sold nearly 500,000 copies; it was later placed on numerous hall of fame lists. It influenced game developers such as Bethesda Softworks and Valve Corporation, and it was an inspiration behind the games Deus Ex and BioShock. The game has one sequel: Ultima Underworld II: Labyrinth of Worlds (1993).

Contents |

Gameplay

Ultima Underworld's gameplay is from a first-person perspective in a 3D environment.[1] The player uses a freely movable mouse cursor to interact with the game's world and the icon-based interface of the heads-up display (HUD). For example, the Look icon allows the player to examine objects closely, and the Fight icon causes the player character to ready the currently held weapon.[1][2] An inventory accessible from the HUD lists currently carried items and weapons; capacity is limited by weight.[2] Players equip items by dragging them onto a representation of the character in a paper doll system.

The game takes place entirely in a large, multi-level dungeon. Progression is non-linear, allowing the player to explore areas and to finish puzzles and quests in any order.[3] Exploratory actions include looking up and down, jumping, and swimming.[4][5] The player character may carry light sources to extend the line of sight in varying amounts.[3] An automatically filling map, to which the player can add notes, records what the player has seen above a minimum level of brightness.[6]

The player begins the game by creating a character and selecting traits including gender, class and skills. Skills range from fighting with an axe and bartering to picking locks. The character gains experience points through combat, quests and exploration; when a certain number of points is accumulated, the character levels up and gains hit points and mana. Experience allows the player to recite mantras at shrines in the game; each mantra increases a specific skill. Mantras are statements, such as "Om Cah", which the player types into the text interface that appears when the Talk option is used on a shrine. Simple mantras are provided in the game's manual; more complex ones are hidden throughout the game.[3]

The developers intended the game to be a realistic and interactive "dungeon simulation", rather than a straightforward role-playing game. For example, many objects in the game have no actual use,[6] while a lit torch may be used on corn to create popcorn.[7] Weapons deteriorate with use, and the player character must eat and rest; light sources burn out unless extinguished before sleeping.[3] A physics system allows, among other actions, for items to bounce when thrown against surfaces.[4] The game contains non-player characters (NPCs), with whom the player can interact by selecting dialogue choices from a menu. Most NPCs have possessions and are willing to trade them.[1] The game was designed to give players "a palette of strategies" with which to approach situations, and its simulation systems allow for emergent gameplay.[8][9]

Combat occurs in real-time; the player character and certain opponents can use melee and ranged weapons. The player attacks by holding the cursor over the game screen and clicking, depressing the button longer to inflict greater damage.[1] Some weapons allow for different types of attacks, depending on where the cursor is held; for example, clicking near the bottom of the screen may result in a jab, while clicking in the middle produces a slash.[3] Enemies sometimes try to escape when near death.[4] The game's rudimentary stealth mechanics may occasionally be used to avoid combat altogether.[9] The player may also cast spells by selecting an appropriate combination of runestones. Like mantras, runestones must be found in the game world before use. There are over forty spells, some undocumented;[7] their effects range from causing earthquakes to allowing the player character to fly.[1]

Plot

Setting

Ultima Underworld is set in Britannia, the fantasy world of the Ultima series. Specifically, the game takes place inside a large, underground dungeon known as the Great Stygian Abyss. The dungeon's entrance sits on the Isle of the Avatar, ruled by Baron Almric. The Abyss first appeared in Ultima IV: Quest of the Avatar, in which it contained the player's final goal, the Codex of Ultimate Wisdom.[10]

Ultima Underworld is set after the events of Ultima VI: The False Prophet; in the time between the two games, a man named Cabirus attempted to create a utopian colony inside the Abyss. The eight settlements of the Ultima series each embody a virtue, and Cabirus wished to create a ninth that embodied all virtues. To achieve this, he united diverse cultures and races in peaceful co-existence and planned to promote harmony by giving each group one of eight virtue-imbued magical artifacts. However, he died before distributing the artifacts, and left no instructions for doing so. As a result, the colony collapsed into anarchy and war, and the artifacts were lost.[10] At the time of Ultima Underworld, the Abyss contains the remnants of Cabirus's colony, with fractious groups of humans, goblins, ogres and others living there.[10][11]

Story

Before the beginning of the game, the Abyss-dwelling wizard brothers Garamon and Tyball accidentally summoned a demon, the Slasher of Veils, while experimenting with inter-dimensional travel. Garamon was used as bait to lure the demon into a room imbued with virtue. However, the demon offered Tyball great power if he were to betray Garamon. Tyball agreed, but the betrayal failed; Garamon was killed, but was able to seal the demon inside the room. Because he lacked virtue, Tyball could not re-enter by himself, and planned to sacrifice Baron Almric's daughter at the doorway to gain entrance.[12]

In the game's introduction, the ghost of Garamon haunts the Avatar's dreams with warnings of a great danger in Britannia.[13] The Avatar allows Garamon to take him there,[14] where he witnesses Tyball's kidnapping of Baron Almric's daughter. Tyball escapes, leaving the Avatar to be caught by the Baron's guards.[15] The guards take him to the Baron, who banishes him to the Great Stygian Abyss to rescue his daughter.[16] After the introduction, the Avatar explores the dungeon and finds remnants of Cabirus's colony.[3] A few possible scenarios include deciding the fate of two warring goblin tribes, learning a language, and playing an instrument to complete a quest.[7][11][13] The Avatar eventually defeats Tyball and rescues the Baron's daughter.[12][17]

Development

Ultima Underworld was conceived in 1989 by Origin Systems employee Paul Neurath, after he had finished work on Space Rogue. According to Neurath, Space Rogue "took the first, tentative steps in exploring a blend of RPG and simulation elements, and this seemed to me a promising direction". He felt that the way it combined the elements was jarring, however, and believed that he could create a more immersive experience.[18]

Neurath had enjoyed computer role-playing games (CRPGs) like Wizardry, but disliked their simple, abstract visuals.[19] He believed that Dungeon Master's detailed first-person presentation was a "glimpse into the future", and sought to create a fantasy CRPG that would "bring even more immediacy".[19] In 1990, Neurath wrote a design document for a game titled Underworld.[18] He contracted former Origin employee Doug Wike to create concept art, and assembled a company named Blue Sky Productions to create the game.[19] Among the company's first employees were Doug Church and Dan Schmidt, who had just graduated from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.[19] The core team was thus composed of Doug Church and Dan Schmidt as programmers, Doug Wike as lead artist and Paul Neurath as lead designer.[8]

An early development difficulty was the implementation of texture mapping. Neurath had experimented unsuccessfully with the concept in the late 1980s on an Apple II computer, but believed that the more powerful IBM PCs of the time could feasibly run an implementation. He contacted programmer Chris Green, who implemented a working algorithm.[18][19] After a month of work, the team had a prototype based on the Space Rogue engine, which it featured at the 1990 Consumer Electronics Show (CES).[8][20] Neurath described the prototype as "fast, smooth, and [having] true texture mapped walls, though the ceiling and floor were flat shaded and the corridors and rooms were all 10' [3.0 m] high—it looked a lot like Wolfenstein-3D in fact".[6] The team began to pitch a thirty-second demonstration clip of the game to potential publishers, and reached an agreement with Origin Systems in summer 1990.[20] Origin's Richard Garriott suggested reworking the game to fit into the Ultima universe; until Ultima VI, the series featured first-person dungeon exploration, a concept that Garriott still wished to use.[11] The team agreed, and the game was renamed Ultima Underworld.[19]

Over the next eighteen months, the team created a new engine that could display a believable 3D world, with the concept of varying heights and texture-mapped floors and ceilings. However, Neurath stated that "comparatively little [of this time] was spent on refining 3D technologies. Most was spent working on game features, mechanics, and world building".[6] Their ultimate goal was to create the "finest dungeon game, a game that was tangibly better than any of the long line of dungeon games that came before it".[6] Each member of the small team assumed multiple roles; for example, the game's first two levels were designed by Paul Neurath, and the rest by "a variety of programmers, artists, and designers on the team".[19]

Doug Church explained that "the most important thing was the dynamic creation of the game[; ...] there was no set of rules which we followed, or pre-written plan. We started with the idea of a first-person dungeon simulation [and] as the game was worked on, people would suggest behaviours and systems, and we would all try and figure out how to do it."[6] "We wrote four movement systems before we were done, several combat systems, and so forth," Church later said. "The programming team was mostly just out of school and new to game writing, so we were improvising almost the whole time."[20] The game's dynamic development also resulted in failed experiments, such as "writing [AI] code for many ideas which turned out to be largely irrelevant to the actual gameplay".[18]

Origin advanced the company $30,000 to create the game, but the final cost was $400,000. The game was funded partly by Paul Neurath's royalties from Space Rogue and by Ned Lerner, a friend of Neurath. Throughout development, the studio was run on a tight budget.[19] Another issue was the team's relationship with Origin. At first, Garriott enthusiastically supported the project, and was "instrumental in helping integrate the Ultima fictional elements into the game". However, by 1991, the team interacted infrequently with the publisher; in the first eighteen months of development, no one from Origin visited the studio.[8] The two Origin producers assigned to Blue Sky had little involvement with the game's development, and both left the project after a short time. There were rumors that Origin would terminate the project.[19]

The team proposed that Warren Spector, an Origin employee with whom Paul Neurath had collaborated on Space Rogue, become their producer.[19] Spector was previously involved with the project when Neurath and Church had pitched the game's plot and gameplay concepts to Origin, and later said of the change, "The VP of Product Development, Dallas Snell, had assigned Jeff Johannigman to produce the game—much to my chagrin—and I sort of watched jealously from the sidelines ... [and] when Jeff left the company, I begged and pleaded and whined until I was given the assignment of producing the game."[20] In 2000, Neurath wrote, "Warren understood immediately what we were trying to accomplish with the game, and became our biggest champion within Origin. Had not Warren stepped in this role at that stage, I'm not sure Ultima Underworld would have ever seen the light of day".[19] The game released for DOS on March 27, 1992 in North America.

Technology

Ultima Underworld's game engine was written in the C programming language by Dan Schmidt and Doug Church,[8] with the assistance of a small team.[6][10] Chris Green provided the game's texture mapping algorithm,[19] which was applied to walls, floors and ceilings. The engine allowed for walls at 45 degree angles, transparencies, multiple tile heights and inclined surfaces, and other aspects.[6][8] Ultima Underworld was the first video game to implement many of these effects.[21] The game was also the first indoor real-time 3D first-person game to allow the player to look up and down and to jump.[8]

Ultima Underworld uses two-dimensional sprites for characters,[1] but also features 3D objects because the team believed that it "had to do 3D objects in order to have reasonable visuals".[8] The game also uses physics to calculate motion.[4] During the game's alpha testing phase, part of the programming team worked to create a smooth lighting model.[6]

The game's advanced technology caused the engine to run slowly, forcing the team to limit the viewable area by imposing a large HUD.[8] Despite this change, the game's system requirements were still extremely high.[1][2][13] Doug Church later downplayed the importance of the game's technology, stating that "progress is somewhat inevitable in our field ... [and] sadly, as an industry we seem to know much less about design, and how to continue to extend and grow design capabilities". Instead, he claimed that Underworld's most important achievement was its incorporation of simulation elements into a role-playing game.[8]

Reception

| Reception | |

|---|---|

| Review scores | |

| Publication | Score |

| ACE | 938 out of 1000[1] |

| Dragon Magazine | 6 out of 5[5] |

| Datormagazin | |

| Power Play | 94 out of 100[23] |

| Play Time | 95%[13] |

| Pelit | 98 out of 100[24] |

Ultima Underworld was not an immediate commercial success, causing Origin to decrease the game's marketing support.[18] Word of mouth caused sales to reach nearly 500,000 copies.[18][19] Despite the slow adoption, the game received critical acclaim; its 3D presentation and automapping feature were significantly praised.[1][5][23] A point of contention was the story, which some praised and others found lacking.[2][23] In 1993, the game won the Origins Award for "Best Fantasy or Science Fiction Computer Game of 1992'".[25]

ACE called Ultima Underworld "the next true evolutionary step in the RPG genre" and noted that the simulation-style dungeon was "frighteningly realistic". The magazine thought that the game's sprite character models "detract from the dense atmosphere a bit", but ended the review by stating, "If you've got a PC, then you've got to have Ultima Underworld".[1] Dragon Magazine wrote, "To say this is the best dungeon game we've ever played is quite an understatement[, ... and it] will leave you wondering how other game entertainments can ever stack up against the new standards Abyss sets".[5]

Computer Gaming World described it as "an ambitious project [...] not without its share of problems". They praised the game's "enjoyable story and well-crafted puzzles", but disliked its "robotic" controls and "confusing" perspectives, and stated that "far more impressive sounds and pictures have been produced for other dungeon games". They summarized the game as "an enjoyable challenge with a unique game-playing engine to back it up."[2] The magazine later awarded the game "Role-Playing Game of the Year".[26] The Chicago Tribune awarded it Best Game of the Year and called it "an amazing triumph of the imagination [... and] the creme de la creme of dungeon epics".[27]

The game was well received by non-English publications as well. Datormagazin, a Swedish publication, considered the game "in a class by itself".[22] In Germany, Power Play praised its "technical perfection" and "excellent" story.[23] Play Time praised its graphical and aural presentation and awarded it Game of the Month.[13] Finland's Pelit stated that "Ultima Underworld is something totally new in the CRPG field. The Virtual Fantasy of the Abyss left reviewers speechless."[24]

Ultima Underworld was inducted into many hall of fame lists, including those compiled by GameSpy, IGN and Computer Gaming World.[4][28][29][30] PC Gamer US ranked the game and its sequel 20th on their 1997 The 50 Best Games Ever list, citing "strong character interaction, thoughtful puzzles, unprecedented control, and genuine roleplaying in ways that have yet to be duplicated".[31]

Legacy

Ultima Underworld was the first RPG presented in a first-person perspective to use 3D graphics.[21] Gamasutra posited that "all 3D RPG titles from Morrowind to World of Warcraft share Ultima Underworld as a common ancestor, both graphically and spiritually ... [and] for better or for worse, Underworld moved the text-based RPG out of the realm of imagination and into the third dimension".[21] The game's soundtrack, composed by George Sanger and Dave Govett,[10] was the first in a major first-person game to use a dynamic music system, in which the player's actions alter the game's music.[32]

The game's influence has been found in Bioshock (2007),[33] whose designer, Ken Levine, said that "all the things that I wanted to do and all the games that I ended up working on came out of the inspiration I took from [Ultima Underworld]".[34] Gears of War designer Cliff Bleszinski also cited it as an early influence, stating that it had "far more impact on me than Doom".[35] Other games influenced by Ultima Underworld include The Elder Scrolls: Arena,[36] Deus Ex,[37] Deus Ex: Invisible War,[38] Vampire: The Masquerade - Bloodlines,[39] and Half-Life 2.[40] Tony Gard stated that, when designing Tomb Raider, he "was a big fan of ... Ultima Underworld and I wanted to mix that type of game with the sort of polygon characters that were just being showcased in Virtua Fighter".[41]

id Software's use of texture mapping in Catacomb 3D, a precursor to Wolfenstein 3D, was influenced by Ultima Underworld.[21] Conflicting accounts exist regarding the extent of this influence, however. In the book Masters of Doom, author David Kushner asserts that the concept was discussed only briefly during a 1991 telephone conversation between Paul Neurath and John Romero.[42] However, Paul Neurath has stated multiple times that John Carmack and John Romero had seen the game's 1990 CES demo, and recalled a comment from Carmack that he could write a faster texture mapper.[18][43]

Despite the technology developed for Ultima Underworld, Origin opted to continue using traditional top-down, 2D graphics for future mainline Ultima games.[44] The engine was enhanced for Ultima Underworld's 1993 sequel, Ultima Underworld II: Labyrinth of Worlds,[6] and again for System Shock (1994).[45] Looking Glass Studios planned to create a third Ultima Underworld, but Origin rejected their pitches.[18] After EA rejected Arkane Studios' pitches for Ultima Underworld III, the studio created a spiritual successor, Arx Fatalis.[46]

Ultima Underworld was ported to other systems. This first occurred in 1997, when a Japan-only version for the PlayStation console released.[47] In the early 2000s, Paul Neurath approached Electronic Arts (EA) to discuss a port of Ultima Underworld to the Pocket PC. EA rejected the suggestion, but allowed him to look for possible developers; Neurath found that ZIO Interactive enthusiastically supported the idea, and EA eventually licensed the rights to the company. Doug Church and Floodgate Entertainment assisted with portions of Pocket PC development,[8] and the port was released in 2002.[44]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 Upchurch, David (April 1992). "Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss". ACE (55): 36–41.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 Greenberg, Allen (July 1992). "Abyssmal Perspective". Computer Gaming World (96): 42–44.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss Player's Guide. Origin Systems. 1992.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 The GameSpy Staff. "GameSpy's Top 50 Games of All Time". GameSpy. http://archive.gamespy.com/articles/july01/top50index/. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Lesser, Hartley; Lesser, Patricia; Lesser, Kirk (November 1992). "The Role of Computers". Dragon Magazine (187): 59–64.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 6.9 "An Interview With Looking Glass Studios". Game Bytes. 1992. http://www.ttlg.com/articles/UW2int.asp. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Carlson, Rich. "Hall Of Fame: Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss". GameSpy. http://archive.gamespy.com/halloffame/july01/underworld/. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ↑ 8.00 8.01 8.02 8.03 8.04 8.05 8.06 8.07 8.08 8.09 8.10 8.11 Mallinson, Paul. "Games That Changed The World Supplemental Material". PC Zone. http://www.mallo.co.uk/ultima/index.htm. Retrieved March 9, 2009.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Ultima Underworld II: Labyrinth of Worlds Manual. Origin Systems. 1993.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 10.2 10.3 10.4 Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss Manual. Origin Systems. 1992.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 "The Ultima Legacy". GameSpot. http://www.gamespot.com/features/ultima/g18.html. Retrieved March 9, 2009.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Allston, Aaron (1992). Ultima Underworld Clue Book: Mysteries of the Abyss. Origin Systems. ISBN 0929373081.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 13.3 13.4 Geltenpoth, Alexander; Menne, Oliver (June 1992). "Ultima Underworld". Play Time: 20, 21.

- ↑ Looking Glass Studios. Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss. (Origin Systems). (1992) "Ghost: Treachery and doom! My brother will unleash a great evil. Britannia is in peril! / Narrator: Sure that the ghost can take you to Britannia, you allow yourself to be drawn to him."

- ↑ Looking Glass Studios. Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss. (Origin Systems). (1992) "Tyball: No matter, thou shalt serve to draw the hounds from the scent. / Narrator: Below a creature heads toward the dark woods, a thrashing sack slung over its massive shoulder."

- ↑ Looking Glass Studios. Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss. (Origin Systems). (1992) "Baron Almric: If thou art truly the Avatar, then perhaps thou canst offer hope. None here can survive the Stygian Abyss and rescue Ariel. My mind is set! Corwin shall take thee to the Abyss. Return here with my daughter and thy innocence shall be proven. If thou dost not return, Avatar, then thy lie shall have brought thee low."

- ↑ Looking Glass Studios. Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss. (Origin Systems). (1992) "Baron Almric: Thou hast earned my gratitude and more. Were it not for thee, my daughter tells me we would have lost more than her delightful company."

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 18.4 18.5 18.6 18.7 Mallinson, Paul (April 16, 2002). "Feature: Games that changed the world: Ultima Underworld". Computer and Video Games. http://www.computerandvideogames.com/article.php?id=28003. Retrieved February 10, 2009.

- ↑ 19.00 19.01 19.02 19.03 19.04 19.05 19.06 19.07 19.08 19.09 19.10 19.11 19.12 Neurath, Paul (June 23, 2000). "The Story of Ultima Underworld". Through the Looking Glass. http://www.ttlg.com/articles/uw1.asp. Retrieved February 12, 2009.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 Hallford, Jana (June 7, 2001). Sword & Circuitry: A Designer's Guide To Computer Role-Playing Games. Cengage Learning. 61–63. ISBN 0761532994.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Shahrani, Sam (April 25, 2006). "Educational Feature: A History and Analysis of Level Design in 3D Computer Games (Part 1)". Gamasutra. http://www.gamasutra.com/view/feature/2674/educational_feature_a_history_and_.php?page=1. Retrieved February 10, 2009.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Fröjdh, Göran (May 1992). "Tjuvtitten Ultima Underworld". Datormagazin: 66.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 23.3 Hengst, Michael (June 1992). "Das ultimative Dungeon". Power Play.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Nirvi, Niko (February 1992). "Virtuualifantasian mestarinäyte". Pelit: 22-24. ISSN 1235-1199.

- ↑ "1992 List of Winners". Origins Game Fair. http://www.originsgamefair.com/awards/1992. Retrieved February 26, 2009.

- ↑ "CGW Salutes The Games of the Year". Computer Gaming World (100): 110, 112. November 1992.

- ↑ Lynch, Dennis (January 29, 1993). "Winners and worsts From Corn Gods to Bart Simpson, a look back". Chicago Tribune: 59. http://pqasb.pqarchiver.com/chicagotribune/access/24318432.html?dids=24318432:24318432&FMT=ABS&FMTS=ABS:FT&date=Jan+29%2C+1993&author=Dennis+Lynch.&pub=Chicago+Tribune+(pre-1997+Fulltext)&desc=Winners+and+worsts+From+Corn+Gods+to+Bart+Simpson%2C+a+look+back&pqatl=google. Retrieved March 17, 2009.

- ↑ "The Top 25 PC Games of All Time". IGN. July 24, 2000. http://pc.ign.com/articles/082/082486p1.html. Retrieved March 6, 2009.

- ↑ "IGN's Top 100 Games (2005)". IGN. http://top100.ign.com/2005/091-100.html. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ↑ "150 Best (and 50 Worst) Games of All Time". Computer Gaming World (148). November 1996.

- ↑ "The 50 Best Games Ever". PC Gamer US. May 1997.

- ↑ Brandon, Alexander (2004). Audio for Games: Planning, Process and Production. New Riders Games. 88. ISBN 0735714134.

- ↑ Weise, Matthew Jason (February 29, 2008). "Bioshock: A Critical Historical Perspective". Eludamos. Journal for Computer Game Culture 2 (1): 151–155. OCLC 220219478. http://www.eludamos.org/index.php/eludamos/article/view/27/40. Retrieved March 8, 2009.

- ↑ Irwin, Mary Jane (December 3, 2008). "'Games Are The Convergence Of Everything'". Forbes. http://www.forbes.com/2008/12/03/ken-levine-bioshock-tech-personal-cx_mji_1203levine.html. Retrieved March 17, 2009.

- ↑ Totilo, Stephen (May 22, 2006). "Gaming Roundtable Considers Bloody Monsters". MTV. http://www.mtv.com/news/articles/1532185/20060519/story.jhtml. Retrieved March 6, 2009.

- ↑ "Arena: Behind the Scenes". Bethesda Softworks. http://www.elderscrolls.com/tenth_anniv/tenth_anniv-arena.htm. Retrieved 2007-09-28.

- ↑ "Warren Spector of Ion Storm (Part Two)". Eurogamer. August 4, 2000. http://www.eurogamer.net/article.php?article_id=337. Retrieved March 6, 2009.

- ↑ Aihoshi, Richard (November 17, 2003). "Deus Ex: Invisible War Interview, Part 1". IGN. http://rpgvault.ign.com/articles/440/440693p1.html. Retrieved March 6, 2009.

- ↑ Boyarsky, Leonard (December 13, 2003). "Vampire: The Masquerade - Bloodlines Designer Diary #3". GameSpot. http://www.gamespot.com/pc/rpg/vtmb/news.html?sid=6085643&mode=previews. Retrieved March 8, 2009.

- ↑ Reed, Kristan (May 12, 2004). "Half-Life 2 - Valve speaks to Eurogamer". Eurogamer. http://www.eurogamer.net/articles/i_e3valvesoftware_pc. Retrieved March 6, 2009.

- ↑ Gibbon, Dave (June 28, 2001). "Q&A: The man who made Lara". BBC. http://news.bbc.co.uk/2/hi/entertainment/1410480.stm. Retrieved March 6, 2009.

- ↑ Kushner, David (2003). Masters of Doom: How Two Guys Created An Empire And Transformed Pop Culture. Random House. 89. ISBN 0375505245.

- ↑ James Au, Wagner (May 5, 2003). "Masters of "Doom"". Salon.com. http://dir.salon.com/story/tech/feature/2003/05/05/doom/index.html. Retrieved March 9, 2009.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Barton, Matt (April 11, 2007). "The History of Computer Role-Playing Games Part III: The Platinum and Modern Ages (1994-2004)". Gamasutra. http://www.gamasutra.com/features/20070411/barton_02.shtml. Retrieved March 7, 2009.

- ↑ Shahrani, Sam (2006-04-28). "Educational Feature: A History and Analysis of Level Design in 3D Computer Games (Part 2)". Gamasutra. http://gamasutra.com/features/20060428/shahrani_01.shtml. Retrieved 2009-02-10.

- ↑ Todd, Brett (2002-03-20). "Arx Fatalis Preview". GameSpot. http://www.gamespot.com/pc/rpg/arxfatalis/news.html?sid=2856384&mode=previews. Retrieved February 9, 2009.

- ↑ "GameSpy: Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss". GameSpy. http://cheats.gamespy.com/playstation/ultima-underworld-the-stygian-abyss/. Retrieved March 7, 2009.

External links

- Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss at MobyGames

- "Descending into the Abyss: A Storyteller explores the narrative accomplishments of Ultima Underworld: The Stygian Abyss" -(from Well Played 1.0)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||